One of the unjustified criticisms of nuclear energy for Ireland is that we couldn’t afford the large cost involved. While it is hard to defend the enormous capital cost of the very large nuclear station being built at Hinkley Point in Britain, Ireland is unlikely to build such a station. Instead, we are likely to wait a year or two until smaller, cheaper and even safer plants become available and economically attractive to our relatively small island.

One way to assess whether nuclear is economically attractive to us is to understand the economics of other low-emission technologies, one of which is solar energy. The costs of Solar Photovoltaic (Solar PV) panels have fallen dramatically in recent years, so it is time to have a look at the figures as they might apply to Ireland in 2018.

Perceived benefits

The 2017 Irish Solar Energy Association Annual Conference in November heard that there is €1 billion of investment in solar technology planned for Ireland. The suggestion was that rooftop solar panels in schools would enable communities to see tangible benefits and the resulting long-term energy savings should go directly to the schools. Enabling this would create 7,000 direct jobs, save the exchequer €210 million a year, and maintain Ireland’s attractiveness for foreign investment. A spokesperson said that, as a taxpayer, he was really concerned about the prospect of annual fines of up to €420 million facing Ireland.

Solar farm or rooftop?

There are two different scenarios at play here – solar farms and rooftop solar.

Most of the current planned investment is for large-scale solar farms that require dedicated land banks and export electricity to the grid. These solar farms are subject to the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). However, rooftop solar has higher maintenance costs and normally supplies the building supporting the roof with only the excess electricity being exported to the grid. These are non-ETS solar schemes.

Solar energy farms involve large arrays of solar panels over a number of acres of land, as in Figure 1 below. A recent project in Northern Ireland, for example, concerns a 5 MW solar farm being installed on 33 acres for a reported £7 million. The owner, a large user of electricity, says that the electricity produced will be worth over £500k per year. This confirms that it will operate at around 10% capacity factor. [5MW capacity, 10% capacity factor, £118 per MWh, 8760 hours per year yields £517k per year].

Excluding maintenance costs of at least £70k per year and interest, legal, insurance and other overheads, the project appears to return £517k on a capital investment of £7 million. This would be an unacceptably low return on investment of 7.4% from which to fund the above costs and repay the capital.

Would placing solar panels on the rooftops of schools – who pay more for their electricity – make more economic sense? The downside here is that schools are only open for 183 days per year at primary level and 167 days per year at post-primary level and are normally closed during most of the summer season when solar panels are producing most of their energy.

If schools were to use 20% of the annual solar energy, avoiding the need to pay 20 cent per unit for electricity, and export the remainder at €80 per MWh, that electricity would be worth €456k annually. This is an even less attractive proposition than the solar farm in the previous example, and is not economically viable.

Value of electricity produced

Using the examples above, €1 billion would buy 632 MW worth of solar farms and produce 550,000 MWh of electricity per year. If this was valued similarly to onshore wind which receives a guaranteed price of €80 per MWh, that electricity would be valued at €44.3 million per year.

This is well short of the €50 million annual interest charge on the capital (at 5% per annum), the estimated €10 million annual maintenance charge and legal and other overheads.

To return reasonable breakeven operating costs of €66 million annually, the solar electricity would need to be priced at €120 per MWh, which is 50% higher than the guaranteed price for electricity from onshore wind. This does not make economic sense.

Value of emissions avoided

On average throughout the year in Ireland, electricity emits 468 grams of carbon dioxide per unit. This can be expressed as 0.468 tons of CO2 per MWh. Although emissions are often lower in summer – when solar energy is at its peak – and solar energy is more likely to displace flexible and cleaner gas rather than dirtier and less flexible coal and peat, using the average figure indicates that 632 MW of solar farms could avoid 260,000 tons of CO2 annually. This has a value to electricity producers who are subject to the Electricity Trading Scheme (ETS).

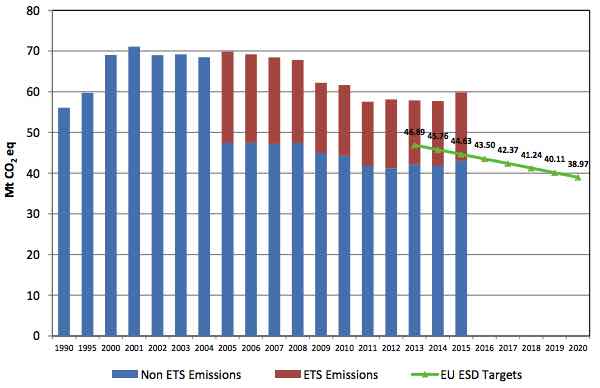

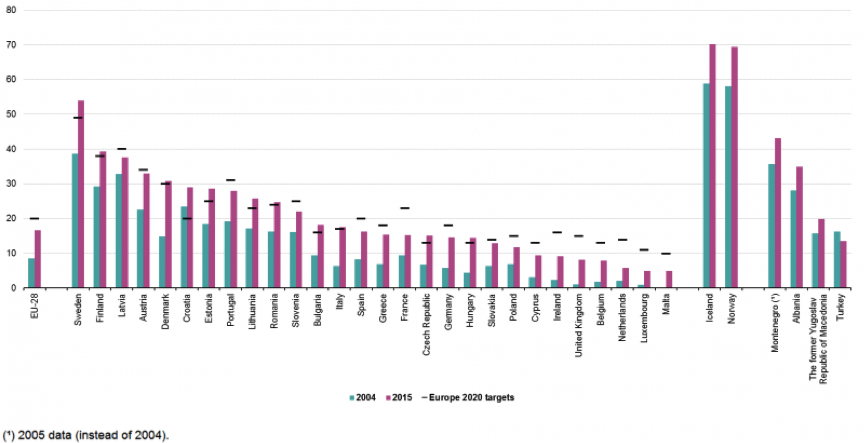

The current market price for CO2 in the ETS has been consistently below €10 per ton since 2011 (see Figure 2 below), so the avoided CO2 would be worth less than €2.6 million. This does not significantly alter the lack of an economic case for solar farms.

Value of increased use of Renewables

For rooftop schemes that fall in the non-ETS sector, there is a value attributed to their use in increasing the amount of renewable energy used in Ireland.

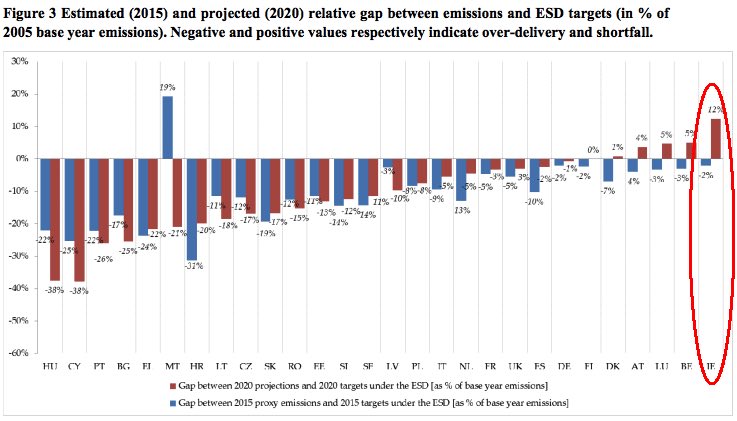

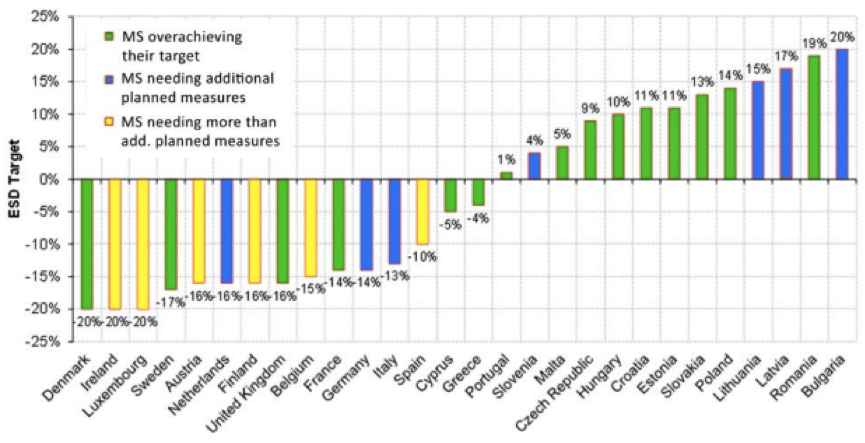

Aside: Although the climate is influenced by greenhouse gas emissions, Ireland’s emissions from electricity are within our allowed limits and lowering these emissions further is of little or no financial benefit to us, as explained above. The same cannot be said for Renewables targets, which are not specifically aimed at reducing emissions. Rather, they are political agreements that are not associated with emissions increase or decrease. To illustrate this point, Figure 3 shows how the United Kingdom is on track to exceed its climate change target of an emissions reduction of 16%. But Figure 4 shows that it is failing to meet its political target of 15% of energy from Renewables and may be fined as a result. End Aside

Nonetheless, Ireland has committed to getting at least 16% of our energy from renewables by 2020 and will probably be fined at an estimated rate of approximately €120 million for every % underachieved.

632 MW of rooftop Solar PV could produce 550,000 MWh of electricity per year, supplying around 2% of Ireland’s electricity. As electricity represents around 20% of the energy used in Ireland, this solar energy could contribute about 0.4% of renewable energy to Ireland’s total at a potential value of €50 million. If this penalty has a realistic chance of being avoided, then there may be economic merit in rooftop solar. This aspect could merit further study.

Conclusion

While rooftop solar is less effective and has higher annual costs than solar farms, there is a possibility that it may make more economic sense if it can be used to contribute to Ireland’s renewable energy targets under the EU Effort Sharing Directive. However, the above analysis may not completely capture all the nuances of how Renewables targets are calculated under this Directive, so any corrections in that regard would be very much appreciated.

These calculations take no account of constraints or curtailments required to ensure electricity grid stability – some solar energy may not be usable due to an excess of Renewable electricity available at any time, or other generators may need to act ‘out of merit order’ in order to accommodate fluctuations in intermittent energy sources such as solar or wind. Such constraints costs exceeded €130 million in 2017, so even a 2% increase here would amount to €2.6 million.

Also ignored is the need to repay the €1 billion capital cost. Repaying this cost over 20 years would require €50 million per annum.

Finally, given that solar energy will be near zero at times of our highest demand for electricity – dark, mid-winter evenings – we must retain sufficient non-solar generators to supply our largest electricity needs. This means that solar energy is not technically required to satisfy electricity needs unlike non-solar generators, which are required. Further, as the non-solar generators will have lower load factors as they are displaced by solar energy, their loss of income will need to be made up in some way for them to remain in business. These extra costs are also ignored in the above analysis.

There is quite an amount of detail behind this analysis of a complex topic, so I’m open to query on any or all of it. But, the conclusion for now is that solar PV farms do not appear to have an economic case for Ireland in 2018.